In Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes, “To be born a woman has been to be born, within an allotted and confined space, into the keeping of men”[1]. Laura Mulvey finishes this thought three years later in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”[2] -- “Women then stands in patriarchal [visual] culture as a signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his fantasies and obsessions through linguistic command by imposing them on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning.” Berger, again: “One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear.”

This objectification of women in visual culture becomes strikingly apparent when we examine one of the most popular subjects in European art: the reclining nude. It is again worth referencing Berger here when he notes, “To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude...Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display”[3]. Mulvey also argues, “In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong erotic and visual impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness”[4].

What Berger and Mulvey point to is the erasure of the women’s agency. When a woman appears as a reclining nude, most of the time she has been created by men, for men. The woman’s identity is wholly besides the point -- her existence is predicated on how a male artist sees her, and how he renders her for the male viewer: timeless (thus ageless), fully-frontal and ready to be surveyed. Her nudity “is not an expression of her own feelings; it is a sign of her submission to the owner’s feelings or demands”[5].

With these depressing realizations, it is tempting to write off the reclining nude as subject that exists to dehumanize women, proliferated over the centuries under the guise of aesthetic appreciation. But when the subject is explored by women, the results are markedly different. Although a woman can certainly objectify other women and herself, it is much more difficult (and self-defeating) to erase her own agency while creating work related to her body, or that of other women (especially if you are aware of the oppression of women as a whole.) This paper will examine three artists, Suzanne Valadon, Joan Semmel, and Audrey Wollen, and how each artist challenges and subverts the tradition of the reclining nude, and ultimately, the ever-present male gaze.

Before discussing their work, I want to quickly return to the male-dominated canon, and talk about two artists who began to subvert, but ultimately upheld, the objectification of the women in the reclining nude: Edouard Manet and Amedeo Modigliani.

FIGURE 1: Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

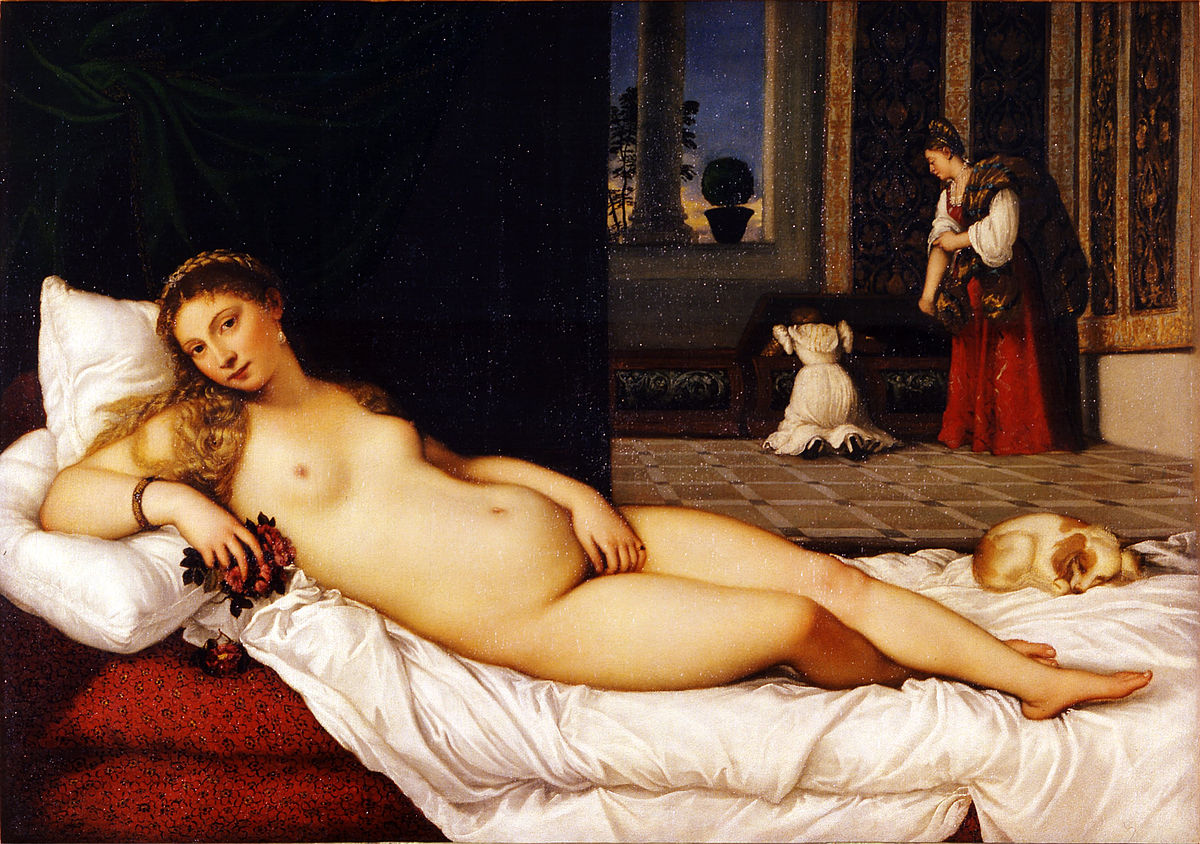

Figure 2: Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas, 119.20 x 165.50 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Manet’s Olympia [Figure 1], a reclining nude shown in the Salon of 1865, was completely panned by critics. It was based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534) [Figure 2], a sexualized update to Giorgione’s Dresden Venus (1510-11). While Titian’s Venus is meant to please with her willing and eager sexuality, Manet’s Olympia is more reticent. Both women stare directly at the viewer, but Olympia’s look is one of ambivalence or annoyance rather than desire, forcing the voyeur to acknowledge his gaze. While Venus is gesturing to her genitals, a suggestion of the auto erotic, Olympia is blocking them with her hand. In fact, what most rankled the critics was Olympia’s body. One critic described it as “like a corpse on the counters of the morgue...dead of yellow fever and already arrived at an advanced state of decomposition”[6]. Unlike Venus with her full, pear-shaped figure and rosy skin, Olympia has a realistic, even too thin, figure with no midtones, making her seem flat and cold. Manet’s Olympia is clearly a direct challenge to the reclining nude traditions set by Titian and others.

However, Olympia never transcends her objectification. Though she suggests personhood by a realistic and authentic emotional reaction to the viewer, Olympia is typecast in one of the limited roles given to women in art: a prostitute. In 1865, Titian’s Venus (Manet’s inspiration) was believed to be a courtesan, and ‘Olympia’ was a pseudonym favored by sex workers in Manet’s time[7]. The black cat is another clumsy reference to female genitals[8]. There are other cues that suggest her vocation: the flowers, perhaps from a client, the flower behind her hair, and her luxurious and exotic accessories[9].

Sex workers were a favorite subject of the impressionists, and Manet is intentionally calling attention to these women who operated on the fringes of bourgeois society, as if calling out the male viewer by confronting him with a more realistic version of his secret liasons, or perhaps not so secret, liasons.

What is lost to the viewer is the fact that the woman who posed for Olympia was a painter herself. Though she may not have allowed such a thing to occur, did it ever cross Manet’s mind to do a painting of Victorine Meurent as she is, rather than cast in a traditional role of service? And, as Charles Bernheimer points out in “Manet’s Olympia: The Figuration of Scandal”, “...however critically Manet’s painting may comment on the male gaze, it does not subvert the gender of that gaze”[10]. This is still a reclining nude by man, for man.

Amedeo Modigliani is famous for his reclining nudes, and that is because he too subverts the conventions of the genre. While his nudes reference Italian masters like Titian and Giorgione, they are highly stylized. “Reduction and abstraction are Modigliani’s main means of creation,” Doris Krystof writes[11]. Hardly proportional, they are almost more about shapes than the figures (“The sparing use of colour...is evidence of the strong concentration on formal demands”)[12]. Most noticeably -- they have pubic hair. This was the offensive detail that caused his only solo show to be shut down for indecency[13]. Once you’ve seen a Modigliani, you can’t help but notice the obvious lack of hair on academic or classical nudes, and appreciate how radical this addition is.

Figure 3: Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché, 1917, oil on canvas.

The pubic hair points us to another reason Modigliani’s show was cancelled: his reclining nudes are overtly sexual. Unlike Titian’s Venus [Figure 2], where the viewer is given clues that she is married (like the wedding chest and the dog)[14], there is hardly a background in Modigliani’s work. The woman and her sexual desire is the painting, and the “cropped composition gives the viewer the impression that he is standing directly in front of the model”[15].

Modigliani’s women exist to please, to be admired, to be displayed. Nu Couché [Figure 3], which recently sold for $170 million[16], is no portrait -- it is an idealized figure, perhaps based on a real person, but reduced to an abstraction. A slight smile even indicates that she enjoys her objectification: truly an idealized woman. As art historian Giovanni Scheiwiller puts it, the nudes represent “a completely spiritual unity between the artist and the creature he has chosen as his model”[17]. Modigliani has completely absorbed, or perhaps erased, the individuality of his model. She has become the object, the creature, of his fantasy, and the fantasy of the male viewer.

It is difficult to study the history of reclining nudes created by women because there are so few to choose from. Women were denied access to formal art training until the 19th century, and then only middle-class women were allowed entrance. Even among that group, the social taboos associated with studying the nude figure as a woman were too great to be overcome by most.

Suzanne Valadon was an exception. Her work as an artist’s model disqualified her from the respectable route of the ‘woman-artist,’ like Cassatt or Vigée Le-Brun. A model was considered deviant in 1880s Paris by respectable society, because the sexual relationship between the artist and the model was a fetishized source of creativity[18]. Valadon had sexual and non-sexual relationships with various artists that she modelled for, including Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, two artists who encouraged her to draw and display her work[19]. Because she was not within the realms of respectability, she was able to study and “work within the male-defined iconography of the nude"[20].

Figure 4: Suzanne Valadon, Nude Getting into bath beside the seated grandmother, 1908.

Valadon’s early nude drawings were not reclining, but rather individual women engaged in activities. Compared to the static and timeless Venus, Valadon tried to capture “the intensity of a particular moment of action”[21]. This interest in a single moment in time was seen among her contemporaries, including Degas and Lautrec[22], but their compositions, and their visual styles, couldn’t have been more different. Although this paper concerns reclining nudes, which Valdon did not paint until the 1920s and 30s, it is worth noting the difference between the nude women in her early drawings versus those created by her male peers.

Valadon’s women are usually seen getting into baths or getting dressed, often from a distant and artificially high angle [Figure 4.] “The effect is to flatten and to distort space so that the spectator is offered no ideal viewing position from which to look a the nude figure of the woman.” Her drawing style is linear and harsh, very different from the soft, pastel nudes of Degas, and they are usually uncomfortably or awkwardly posed[23]. Worse yet for the male viewer is that the naked woman is usually not alone, but shown in a social relationship with another woman, often older and clothed. Betterton concludes, “Valadon’s nudes, in showing women’s nakedness as an effect of particular circumstances and as differentiated by age and work, therefore challenge the idea that nakedness is essence, and irreducible quality of the ‘Eternal Feminine'[24].

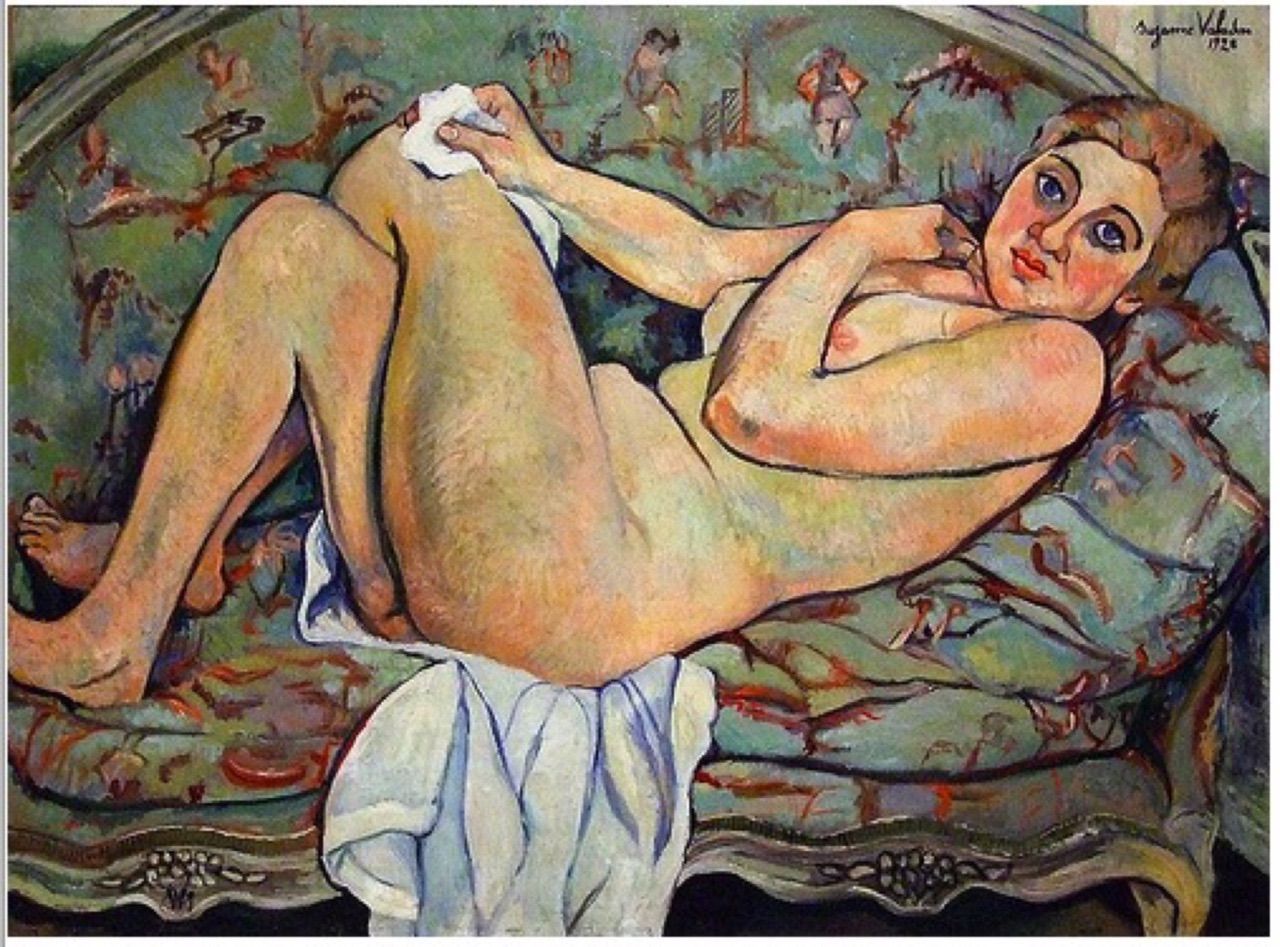

Figure 5: Suzanne Valadon, Reclining Nude, 1928, oil on canvas.

Figure 6: Suzanne Valadon, Reclining Nude on a leopard skin, 1923, oil on canvas.

Like her contemporaries, Valadon’s reclining nudes of the 1920s and 30s draw from the iconography established by the Italian masters and others. But what is different about Valadon’s work is how they are simultaneously nudes and portraits. The attention to detail is uncompromising, and the women’s faces are just as strong and distinct as the rest of the figure. Valadon does not idealize women’s bodies, but shows them as they truly are [Figure 5 & 6.] One critic even accused of her misogyny for her refusal to idealize women’s bodies, but as Betterton points out, “Embedded within such critical confusions is the clear assumption that the aesthetic value of the nude is bound up in the sexual desirability of the model"[25]. Valdon was interested in models of different sizes, ages, and classes, and because of that her work “offers us a way of looking at the female body which is not entirely bound in the implicit assumption that all such images are addressed only to a male spectator"[26].

In the 1970s, artist Joan Semmel continued the conversation about the male and female gaze through her use of her own nude body in her work. Though she started as an abstract expressionist painter, she turned her attention to the figure, “prompted by a need to work from a more personal viewpoint and charged by my then-emerging consciousness as a feminist”[27]. This led her to “the most literal possible interpretations of female self-determination, a first person definition of self"[28].

Pink Fingertips (1977) [Figure 7], created from a black and white photograph of her own reclining, naked body, takes back the gaze by operating from this first-person perspective. “I went into the idea of myself as I experience myself, my own view of myself. What I was trying to get there was first all of the self, the feeling of the self, and the experience of one’s self”[29]. It is a photorealistic painting of her own body, looking down at herself, with a foreshortened upper torso and breasts. Her forefinger is pointing towards her vagina, suggesting masturbation[30]. There is eroticism here, but it’s not idealized. This is not a reclining nude dreamt up for a man, it is a rather surreal self-portrait, an undeniable statement of individual sexuality.

Figure 7: Joan Semmel, Pink Fingertips, 1977.

Figure 8: Joan Semmel, Mythologies and Me, 1976. Oil and collage on canvas.

A year earlier, Semmel created Mythologies and Me [Figure 8], which directly addressed women’s objectification in visual culture. In a triptych with five foot high panels, she situates “an image of her nude body between a pin-up girl with spread legs and full breasts, and an image adapted from Willem de Kooning’s Woman Series”[31]. Unlike the women on either side of her, “Semmel turns herself away from the spectator, her thighs open in the opposite direction, for this is a woman gazing at her own nude body"[32]. She further defuses the male gaze by her alterations to the images on either side of her, adding a humorous rubber nursing nipple to the de Kooning parody, and covered up the genitals of the woman in the photograph by adding a feather boa. Her reclining nudes are radical because they upset the idea that nudes exist in art purely for male pleasure. The subject is in control of her own sexuality, and is aware of her ability to deny the viewer titillation if she so chooses.

Figure 9: Audrey Wollen, Untitled reclining nude, part of the Repetition series, 2015.

Finally, contemporary artist Audrey Wollen shows us that there are still new ways of addressing and challenging the harmful iconography of the reclining nude. Her work is often in conversation with visual culture, such as her photographic ‘Repetition’ series, where she riffs upon works like Botticelli’s the Birth of Venus and other classics by imitating the poses in contemporary settings. Among this self-portraiture is a reclining nude [Figure 9], a re-creation of Velazquez's The Rokeby Venus (1651.)

The reclining nude in this image cannot just be a nude to be surveyed, because her individuality is defined by her surroundings and her agency. She is obviously in her bedroom, an anime poster and other momentos dot the wall. Her feet are kind of dirty, a sign that she has a life outside of this image. Most notably, her head is turned completely away from us -- she is looking at herself through a webcam on her computer. The viewer cannot help but feel they are intruding on a private moment (of self admiration?), and perhaps through the webcam she can see our transgression. Even if she has noticed our gaze, she is ignoring us, especially if we’re male.

Although most reclining nudes throughout history have been created to satisfy male desire, nudes created by women show that it is possible to make figurative work of women that avoids objectification and idealization. I would argue that the reclining nudes of Valadon, Semmel and Wollen are superior to those that they are referencing, because in addition to subverting the iconography conceived by their male forebears, they are also creating new ways of representation that speaks to the individuality of the subject of the painting, as well as the artist. Reclining nudes for women by women do not erase the individuality of their subjects. They underline it.

Footnotes:

[1] Berger, John. “3.” Ways of Seeing, BBC/Penguin , 1972, pp. 46–47.

[2] Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, Oxford UP, 1999, pp. 833–844.

[3] Berger, 54.

[4] Mulvey, 837.

[5] Berger, 52.

[6] Clark, T. J. “The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers.” The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, Knopf, 1985, pp. 288–289.

[7] Ibid, 86.

[8] Moffitt, John F. “Provocative Felinity In Manet’s "olympia".” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 14, no. 1, 1994, pp. 21–31., doi:10.1086/sou.14.1.23205579.

[9] Ibid, 24.

[10] Bernheimer, Charles. “Manet’s Olympia: The Figuration of Scandal.” Poetics Today, vol. 10, no. 2, 1989, p. 274., doi:10.2307/1773024.

[11] Krystof, Doris, et al. Amedeo Modigliani, 1884-1920: the poetry of seeing. Taschen, 2015, p. 67.

[12] Ibid, 69.

[13] Ibid, 59.

[14] Moffitt, 22.

[15] Krystof, 71.

[16] Jones, Jonathan. “Sex sells: why Modiglianis 98-Year-Old hymn to lust is worth $170m.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 10 Nov. 2015, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/nov/10/nu-couche-amedeo-modigliani-sold-for-170m.

[17] Krystof, 60-61.

[18] Betterton, Rosemary. “How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne Valadon.” Feminist Review, no. 19, 1985, p. 11., doi:10.2307/1394982.

[19] Ibid, 15.

[20] Ibid, 14.

[21] Ibid, 15.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid, 16-17.

[24] Ibid, 18.

[25] Ibid, 21.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Marter, Joan. “Joan Semmels Nudes: The Erotic Self and the Masquerade.” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 1995, p. 24., doi:10.2307/1358571.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid, 25.

[30] Ibid, 26.

[31] Ibid, 25.

[32] Ibid.